An Alternative Interpretation of Unusual Communication? Part I

Lately, I’ve been wondering how Douglas Biklen, founder of the Facilitated Communication Institute at Syracuse University (now the ICI), came to think of autism as a motor planning problem, rather than a “neurological and developmental disorder that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave” (as defined by the National Institute of Mental Health). Biklen was not an autism specialist, nor was he trained in psychology or communication sciences and disorders, so where did he get his ideas?

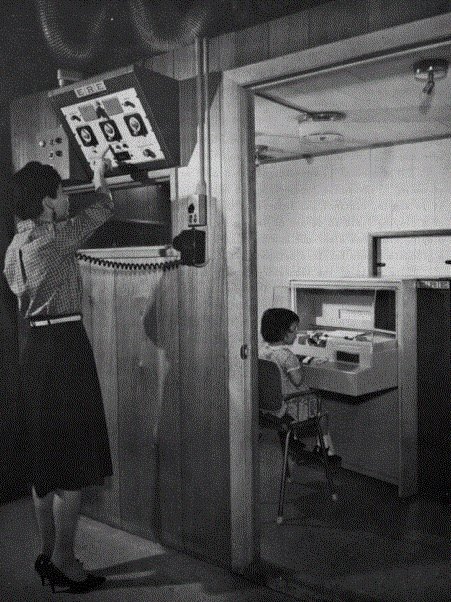

The Edison Responsive Environment (From Omar Khayyam Moore, Autotelic Responsive Environments and Exceptional Children, 1963).

In his 1990 article, Communication Unbound: Autism and Praxis, Biklen introduced the idea of “an alternative interpretation of unusual communication.” To convince people that Facilitated Communication (FC) worked to unlock individuals’ (intact) language and literacy skills, Biklen needed to find support for the idea that mutism and unusual speech in individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities was a neurologically based problem of expression which he defined as “praxis.” For him, this was not a technical term, but merely a reference to “an individual’s difficulty speaking or enacting their words or ideas.” Based on Rosemary Crossley’s (still unproven) claims, an individual subjected to FC, he argued, could effectively “bypass problems of verbal expression” and allowed students to type “natural” language.

To emphasize his point, Biklen referred to a “small body of generally ignored literature on educational methods.” He did not elaborate on why the literature was ignored but, in reading the two sources he cited, my guess is the “literature” may have been ignored because the opinions offered were anecdotal and not rigorously vetted (a point the authors of the sources acknowledged, but Biklen seemed to have missed).

The first article, In A Dark Mirror, (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1969) was written by two pediatricians toward the end of their careers “reflecting on events and some lessons learned from thousands of child patients and their parents.” The authors seemed well-meaning and genuinely concerned that “handicapped children” had less access to “preventive health measures, continuing medical care, adequate sensory testing, thoughtful drug management, and flexible educational services” than their neurotypical counterparts.

As part of their work, the Goodwins developed a “responsive” environment for individuals with disabilities at a center outside the conventional classroom using the Edison Responsive Environment Learning System (ERE) and two “talking typewriters.” For reasons that will become clear in a moment, I am hard-pressed to understand why Biklen included this study in his article on FC. The project was not set up as a scientific experiment, revealed nothing conclusive about the characteristics of “responsive” environments for individuals with learning difficulties, and did not discuss FC or motor-planning problems in individuals with autism.

Perhaps Biklen believed that the talking typewriters were a physical manifestation of a person’s speech ability, which he described was like a “dedicated” computer or language device “capable of expressing phrases that have already been introduced aurally.” Could it be that he thought the responsive environment or “talking typewriters” unlocked intact language and literacy skills? (This is not, btw, how language and literacy skills develop. They have to be taught).

Let’s take a closer look at the report.

In 1964-1966, the Goodwins organized a 28-month project using the Edison Responsive Environment (ERE) with the goal of finding out if children with learning difficulties responded as favorably to it as neurotypical children. According to a 1972 article “The Edison Responsive Environment Learning System, Or the Talking Typewriter,” the Talking Typewriter, housed in its own cubicle, was a computerized electric typewriter with visual and audio capabilities. One of the reading programs for use with the typewriter was based on the Behavioral Research Laboratories (BRL) Sullivan Reading Program. The purpose for the Talking Typewriter was “to create an environment where learning will be a successful, enjoyable experience for the student” by allowing the student to “explore, to discover relationships, to progress at his own speed, to receive feedback on the correctness of his response, and to experience success.”

By the Goodwins’ own account, the project was “informal” and not designed as a scientific experiment. In addition, the training background of the three teachers hired to manage the program “was unconventional” and their practices were “imaginative.” The authors do not explain further these unconventional, imaginative practices or explicitly mention FC.

150 children (ages 3 to 16 years) participated in the project. 75 of the students had learning disabilities, 10 had physical disabilities (including two boys with expressive aphasia), and 65 had the diagnosis of childhood autism. The authors urged all parents to “avoid expectations of immediate success, routine reports of progress, or specific improvement.” The students were free to investigate the ERE in their own fashion during sceduled 30 minute sessions.

By design, student interaction with the ERE was not standardized. Some students, for example, visited once or twice while others visited multiple times (e.g., one autistic student returned 224 times). Some, eventually, typed words and sentences, but how the students achieved these skills was not explained.

Along with participating in ERE sessions, many of the children also had access to a faculty of pediatricians, a clinical psychologist, a social worker, remedial reading teachers, speech therapists, and recreational assistants. The authors found it difficult to predict which children would improve and what activities caused the improvement. They attributed progress in learning to “complex social, psychological, and physical factors.” None of these were quantified. Of several children with learning disabilities, the authors wrote:

Many advanced in reading skills, a few were unaffected, and several improved very rapidly in a short time. In none did we attribute success, when it occurred, to the ERE alone: maturation, school, and home experiences were also important.

Biklen, in his article, described the “success” of a boy named Malcolm. He failed to mention that the Goodwins could not pinpoint factors that contributed to that success (of Malcolm and another boy named Joey):

We are fully aware that the improvement in speech in both of these boys for whom therapy was limited to ERE may have been coincidental. We remain hopeful that other aphasic children will have opportunities to explore the Edison Responsive Environment. (Emphasis mine).

Biklen mentioned another boy, John, who, it appears, had pre-existing literacy skills, but exhibited behaviors that excluded him from a conventional classroom (e.g., hyperactivity, jamming food in his mouth, cackling, screaming, mimicking, pushing other children). With one-on-one attention, he, reportedly, began reading his ERE teacher’s typed words during the fifth session. Later, he was able to re-enter school, part-time and with clear expectations of his behavior in the classroom.

Biklen seemed interested in the Goodwins’ comment that the ERE was an “instrument that showed us abilities not measured by conventional psychological tests.”

Since Biklen only partially quoted their thoughts about the ERE, I included it here:

In our experience, the ERE was less an agent for change than a focus for discovery. We learned equally from children who used the instrument eagerly, occasionally, or rarely. There was neither “success” nor “failure” for any child. Each gave guidelines toward better understanding of behavior and levels of competence. Several children had learned to read at an early age with television as the medium for teaching. The ERE was the instrument that showed us abilities not measured by conventional psychological tests. Intervention and school became possible for several who had previously been considered hopeless. Attention to the unmet needs of others invited a crusade.

As enthusiastic and well-meaning as the Goodwins were in attempting to create a responsive educational environment for individuals with disabilities, they ultimately failed to define the characteristics of that environment for the students who participated or to provide reliably controlled evidence that the ERE was, indeed, an instrument to show abilities not measured by conventional psychological tests.

If their goal was to determine if students with learning difficulties responded to the ERE similarly to typically developing students, then they employed the wrong data collecting method (e.g., anecdotes) to answer that question.

Anecdotes, in and of themselves are not a bad thing. Often, a researcher’s idea starts anecdotally with what they see or know—or think they see or know—about any given situation. But, to determine the (scientific) validity of that idea, the researcher needs to set up some controls (e.g., quantify the procedure).

It seems to me that in 28 months and with 150 students, the Goodwins could have discovered quite a lot about the ERE as it related to the participants. What, for example, were the characteristics of the students who exhibited “success” with the ERE? How did they engage with the talking typewriter? Did this change over time? Or, perhaps more importantly, what were the characteristics of the students who avoided the ERE or did not show improvement? What factors contributed to short-term vs. long-term participation in the project? What “unconventional” or “Imaginative” behaviors did the teacher/assistants exhibit in their attempts to engage students in reading or writing? Where techniques used that increased student engagement? Did any decrease student engagement? How did the performance of students with learning difficulties compare with neurotypical students in the same environment? What factors contributed to (or hindered) the “responsiveness” of the environment?

Did this article provide us with an “Alternative Interpretation of Unusual Communication” as Biklen claimed? Uh…no.

Biklen included the Goodwin study in his article Communication Unbound, because, he said, it “did not contradict and may well support” his praxis theory. But, because the Goodwins’ data collection was informal and their discoveries were vague and inconclusive, I cannot see how this article possibly supports his theory. If by chance it does not contradict his praxis theory, it is because the authors did not focus on the issue of motor planning problems in autism in their study.

As a footnote: In 1966, the Goodwins sought expert help from a university hospital to plan a long-term study of communication disorders in children. The plans fell through, they say, due to changes in administration. I cannot help but wonder if the Goodwins had provided their colleagues with reliably controlled data to back up claims of success with the ERE (instead of a report filled with anecdotes and sweeping generalities), would they have met with better results?

Next time, I will review Rosalind Oppenheim’s Effective Teaching Methods for Autistic Children as it relates to Biklen’s article Communication Unbound. I think I may have pinpointed the source for Biklen’s theory about autism as a motor planning problem.