How missed cues and wishful thinking led me astray

I’ve been there, too

Recently proponents of new variants of facilitated communication, Rapid Prompting Method (RPM) and Spelling to Communicate (S2C), have been telling us about the impressions of family members. Family members say they’ve witnessed countless instances of authentic message-passing in naturalistic environments of their PRM and S2C using children. The child’s index finger types out “My teeth hurt” and it turns out she has an abscessed tooth, or “My ears hurt” and it turns out he has an ear infection—even when the person holding the letterboard couldn’t possibly have known.

As a parent who has ushered her kids through the usual course of childhood infections, I suspect that there are all sorts of subconscious cues that we pick up on that tell us that the kid’s not alright, even down to the likely culprit (ear, tooth, throat...), and even if we aren’t consciously aware of either the cues or of what we’re intuiting. Then when the doctor confirms it, it’s easy to forget our initial state of uncertainty: “I knew it was strep throat”, or “Wow, she’s really stoic! I had no idea she was sick.” Or, if the child had earlier typed out the symptom on a held-up letterboard with his index finger: “Wow, he typed ‘my throat hurts’ and I had no idea! That couldn’t have been me directing the message.”

The kind of confirmation bias that we see in this last example, that ever-so-powerful wishful thinking that only a close family member or intimate friend can have, is something that I, too, have experienced. First I had it with deafness; then with autism.

For most of the first year of his life, I was certain that my son wasn't deaf. Yes, he’d had meningitis at five weeks, but it was a mild case, almost certainly viral. Yes, they said he should have a hearing test at nine months, but that was just because of the hyper-vigilance we see everywhere in pediatric medicine. Yes, he’d started babbling at seven months and then stopped. But he couldn’t possibly be deaf. After all, how many times had I tried to tread lightly on the landing while he was napping, only to wake him up? How many times had I snapped a finger behind his back whereupon he promptly turned around? How many times had he crawled over to the NPR-playing radio at the head of our bed and slowly turned the tuning knob until the reception was perfect? Sure, there were times that he didn’t respond to sound, but that must have been because of how absorbed he was with some object. And surely these moments of unambiguous hearing, each one of them vividly imprinted in my memory, outnumbered those other moments of distraction.

So desperately did I want to believe that my son wasn’t deaf that I couldn’t see the non-auditory cues that were staring me in the face: the cues that came from my light treads on the landing, my snapping fingers, and the radio. I leave it to the reader to deduce what those were.

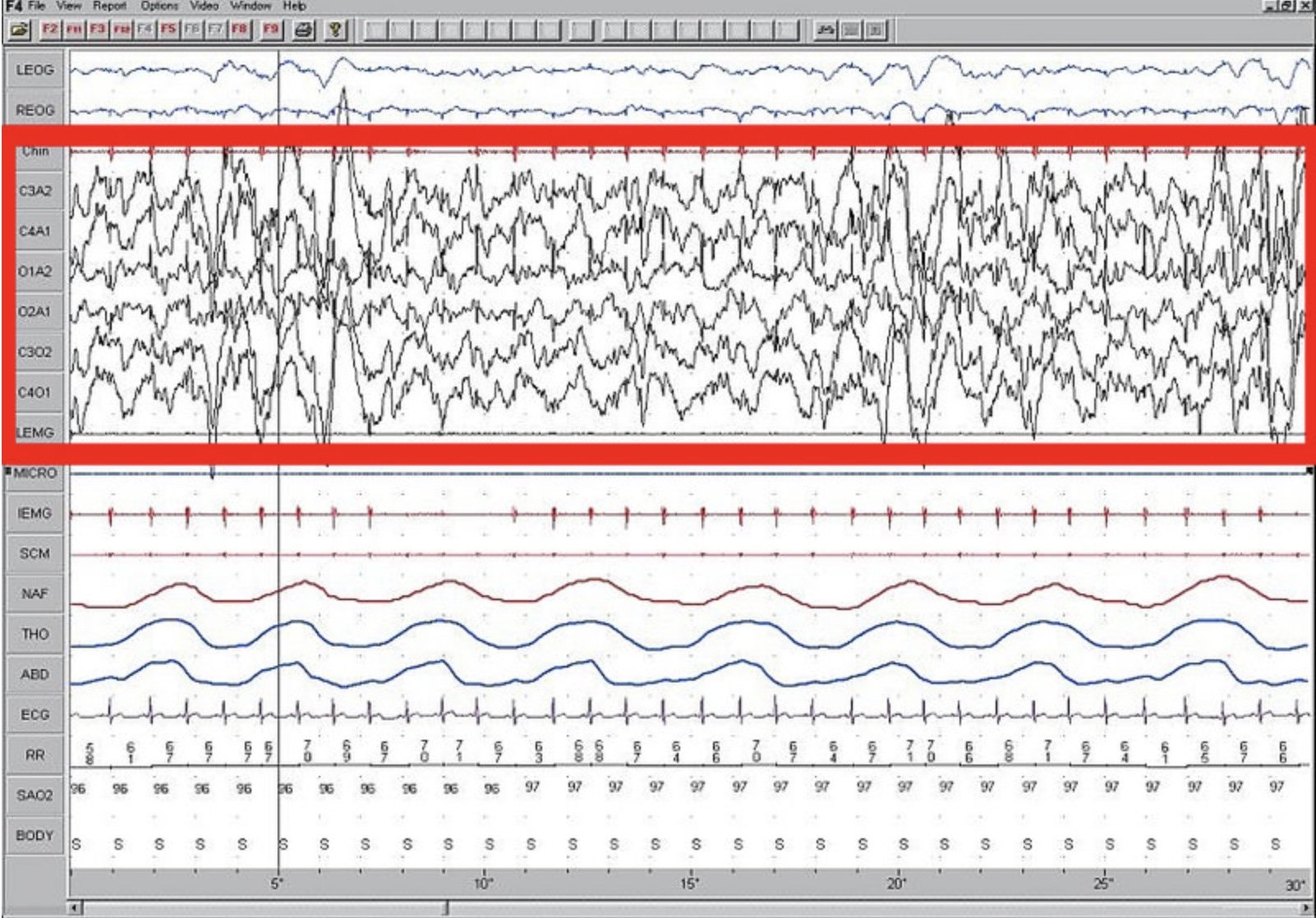

Only an objective test—an Auditory Brainstem Response test that measures the EEG activity of sleeping brains in respond to sounds—convinced me otherwise. And only gradually did this revelation take shape, literally, in the flattening lines of an EEG screen as each next sound frequency was delivered to my son’s brain. Shortly after that, a CT scan showed a malformation of his cochlea, those snail shaped structures that encode sound frequencies and send them to the auditory nerve. The meningitis had played a role, but only as a cue. It had cued the audiologist who prescribed the hearing test; it had not caused the deafness. The Mondini malformation, we learned, is congenital.

Screenshot of EEG during sleep, Wikimedia Commons

Those objective tests, of course, were impossible to argue with, and because of them we snapped into action. First sign language immersion. Then, as soon as he was eligible, cochlear implant surgery. We kept on signing and resumed speaking. He picked up signs; he starting making vowel sounds; slowly he added consonants, then words. And surely that was the end of the story.

Because surely it was those nine months without any linguistic exposure whatsoever and that year and a half with zero access to the speech sounds of the people around him that explained why he was so socially withdrawn.

But deep down, however shocked I was when he got that second diagnosis, through another round of (relatively) objective screening tools, I surely must have sensed that something else was up,

Full blown autism. I knew it all along!

No, I decidedly did not.