What isn’t new: Credulous reporters promoting FC/S2C/RPM

This blog post is a continuation of a series I’m writing in response to a reader’s question: How has FC changed since 1990? I started out wanting to do a simple comparison between the documentary “Prisoners of Silence” and the film “Spellers,” but this proved too complicated. There are just too many issues to cover on the topic. I will provide a recommended reading list and links to relevant blog posts below.

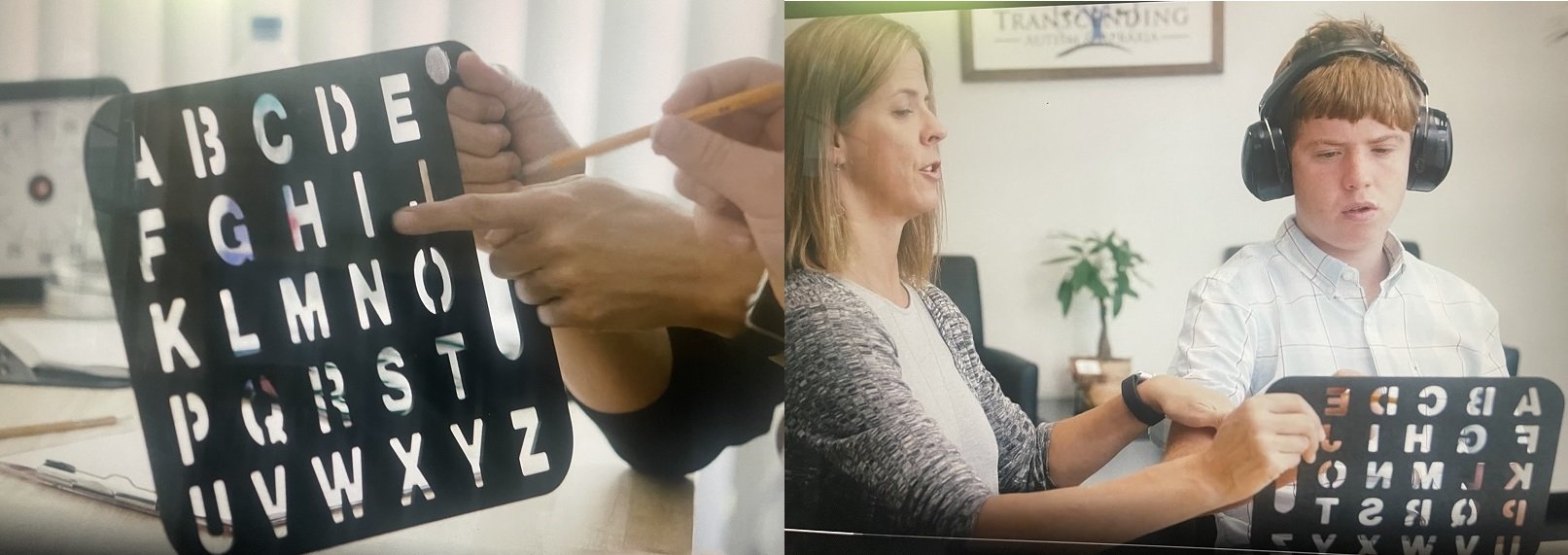

Dawnmarie Gaivin using a form of FC called “Spellers Method” with her son. In the first picture, Gaivin points to the letter I, in the second, she touches her son’s forearm. These physical cues (often inadvertent) aid in letter selection (from Spellers, 2023)

Today, I look at the media coverage of FC/S2C/RPM and how proponents seem to use the popular press to bypass the scientific community, which holds them to a much higher standard than the average news outlet. Indeed, quite a few articles that cover FC/S2C/RPM, including one that was recently published in Forbes, contain little to no critical discussion. As we’ll see, credulous reporting has existed pretty much since FC’s inception.

Consider these select news headlines from the early 1990s (there are many more):

How autistic Chloe stunned the medical world (Toronto Star, 12/21/91)

The Words They Can’t Say (New York Times, 11/3/91)

I AM MNOT RETARDD’ Autistic teen breaks a wall of silence with touch of a finger (The Grand Rapids Press, 11/17/91)

By Typing, Son Spells Love a Letter at a Time; Typing Unlocks a Trapped Mind: ‘I Can Tell Mom I Love Her’ (The Salt Lake Tribune, 12/25/91)

And these contemporary news headlines (there are many more):

Inside the Spellers Method’s Work to Get People Listening to Non-Speakers Everywhere (Forbes, 7/18/24)

How a Miracle Tool Enables Severely Autistic Kids to Communicate for the First Time (New York Post, 12/24/22)

Grace is 14, autistic and ‘smarter than anyone knew.’ (Tampa Bay News, 12/3/20)

And then there are the films and YouTube videos extolling the virtues of FC. Early pro-FC films like Autism is a World and Wretches and Jabberers were much more subtle about their outright rejection of the scientific studies that disprove claims of independent communication than current-day films like Spellers. (see a list of pro-FC films here).

Founder Douglas Biklen looks on while the facilitator stares at the keyboard and the individual being subjected to FC stares at the ceiling. The facilitator “supports” the client near the wrist and at the elbow. (From Prisoners of Silence, 1993).

In fact, Spellers features Dr. Vaishnavi Sarathy brazenly denouncing “the science.” However, in the examples of her facilitating with her son, Sarathy holds a letter board in the air while her son, without looking at the board, pokes a pencil toward it. As with most, if not all, facilitators, Sarathy stares intently at the letter board, (inadvertently) moves the letter board in the air and calls out letters while her son disengages from the activity.

In a 1998 article titled “Facilitated Communication in America: Eight Years and Counting,” Brian Gorman wrote:

FC is amazing because it has surpassed all other junk science fads, affecting families, schools, universities, the law, and even the arts. FC has inspired books, a Frontline expose, a TV movie starring Melissa Gilbert, a play inspired by a CBS 60 Minutes report, an Australian movie based on a book by the creator of FC, in addition to songs and countless poems about breaking the mysterious silence of autism.

In the article, Gorman documents how Douglas Biklen, co-founder of FC and founder of the Facilitated Communication Institute at Syracuse University (now the ICI) bypassed the peer review process integral to scientific study and turned, instead, to popular media to spread the word of his so-called revolutionary discovery. Gorman wrote, “Biklen did not need science because he used the powerful tools of emotion and hope which appealed to his large audience of parents and teachers of disabled children.”

It seems to me that these miracle stories (to this day) often come out during autism awareness month in April and/or around the holidays. Everyone loves a feel-good story to round out the year but these stories are formatted in what I call an “FC credulity sandwich,” which includes a few paragraphs outlining the miracle story—usually someone with profound autism around 12-14 years of age who once struggled but now, with a facilitator holding on to their arm or holding a letter board in the air, can spell out his or her thoughts. The sophisticated spelling seems to surprise the parents or caregivers (but not enough to question authorship). This revelation is followed by a sentence or two mentioning that FC is “controversial” or that “some” skeptics believe facilitators are influencing letter selection followed by another paragraph or two giving readers the impression that even if FC doesn’t work for some, it works for the individual being featured in the story.

From a proponent perspective, this “FC credulity sandwich” seems to serve a few purposes:

It “normalizes” FC use. Most people outside the world of disabilities studies and autism wouldn’t know that FC, with its many pseudonyms, is a facilitator-dependent technique that relies on physical, visual, and auditory cues. They also wouldn’t necessarily know that facilitators and not individuals being subjected to FC are controlling letter selection. They respond emotionally to a story that involves someone who’s struggled but now, seemingly, has overcome their disability.

Workshop leaders use these anecdotes—and the clout of media outlets such as The Washington Post, New York Times, Forbes, and 60 Minutes—to bolster credibility with their workshop participants.

It serves as an effective marketing scheme for proponents who, like Douglas Biklen, want to bypass the scientific process and reach an unsuspecting public.

Breaking the Silence features Soma Mukhopadhyay, her son, and an FC variant called Rapid Prompting Method (CBS News, 2003)

In 2003 (well after Frontline exposed FC as pseudoscience in a 1993 documentary called “Prisoners of Silence”), 60 Minutes advertised Rapid Prompting Method (RPM) when they featured its founder, Soma Mukhopadhyay and her son on an episode titled “Breaking the Silence.” 60 Minutes even admitted in their report that RPM had no basis in science, but they ran the story anyway. Portia Iversen, too, discussed the 60 Minute segment in her book, “Strange Son,” giving us a behind-the-scenes glimpse of how the interview came into being in the first place. (See my reviews of the book here and here). Anyone reading the book can understand that Iversen really, really, really wanted to believe RPM worked. Still, she seemed to have a few pangs of guilt about promoting RPM on a national level. She was, at the time, head of an organization called Cure Autism Now (CAN) that sponsored Mukhopadhyay and her son, Tito, to come to the United States to develop and promote the use of RPM. She was heavily invested—both emotionally and professionally—in getting RPM to “work.” She wrote:

We could not tell parents that their autistic kids might be more intelligent than they suspected when we had no way of helping them get at that intelligence yet. And CAN [Cure Autism Now] was a scientific research foundation. Promoting unproven concepts and methods on national television could be destructive to the foundation’s credibility. (p. 359)

So, instead of getting the interview with Soma cancelled, it seems, Iversen abdicates responsibility for the segment and “blames” Miriam Weintraub, the producer of the segment, for persuading her that “this was a chance of a lifetime, to tell millions of people that autistic kids were intelligent, if only they could be given a way to show it.” (p. 359)

To me, educating the public about the specific challenges many individuals with profound autism and other developmental disabilities face in acquiring language and literacy skills—even with the use of legitimate, evidence-based forms of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)—is one thing. Promoting facilitator-dependent techniques like FC/S2C/RPM that have no reliably controlled evidence to back up claims of independence, call into question authorship, and are highly susceptible to facilitator cueing and control is another. (See Ideomotor Response).

Unfortunately, the 60 Minute segment was so successful that Mukhopadhyay’s popularity increased exponentially. She eventually broke ties with Iversen, found someone else to sponsor her, and moved to Texas to start her RPM business.

For anyone following the Anna Stubblefield case (blog posts here, here, and here), we know the role that the pro-FC, Biklen-produced film “Autism is a World” played in convincing one of Stubblefield’s students (the brother of the victim in this case) that FC worked with people with profound intellectual and developmental disabilities. (It does not. See Katharine’s review of the film here)

Julie Riggott wrote about Autism is a World in an article titled “Pseudoscience in Autism Treatment: Are the News and Entertainment Media Helping or Hurting?”:

In one of this year’s Academy award-nominated films, a severely autistic young woman appears to make a miraculous transformation. Tested with a mental age of a 2-year-old, Sue Rubin had little ability to communicate with the world. When Sue was 13, her mother discovered facilitated communication (FC), a technique in which a facilitator ostensibly helps the autistic person to type. Everything changed. Immediately, and for the first time in her life, Sue could share her thoughts and feelings with her mother. Eventually, she was retested with an IQ of 133 and even enrolled in college—with a facilitator. A brilliant mind was supposedly freed from its prison of silence.

What the documentary doesn’t mention, however, is that FC has a dramatic and highly controversial history that reached a climax more than a decade ago when it was exposed as a pseudoscience.

Part of the reason we started this website was to provide parents, educators, and reporters easy access to systematic reviews, controlled studies, critiques of FC/S2C/RPM, opposition statements, and more. The hope was that people researching this topic wouldn’t have to start from scratch—which, for most, is to give these techniques “the benefit of the doubt.” But, it seems, having easy access to these resources isn’t enough to keep reporters from writing credulous, feel-good, miracle stories that perpetuate the idea that complex communication needs can be cured simply by holding on to someone’s hand or waving a letter board in the air. In rare cases, reporters have put in the work of researching the topic before writing about it (e.g., Jon Palfreman, David Auerbach, Michael Burke), but for the most part, it seems, reporters these days lack the journalistic integrity or intellectual curiosity it takes to call FC out for the pseudoscience that it is.

For those new to FC/S2C/RPM and/or reporters who don’t know what questions to ask about these techniques, here’s an FC Primer and a list of questions that you might consider here and here.

Next time, I’ll be taking a closer look at a recent pro-FC article written by Steven Aquino for Forbes titled “Inside the Spellers Method’s Work to Get People Listening to Non-Speakers Everywhere.”

Recommended Reading:

Auerbach, D. (2015, November 12). Facilitated communication is a cult that won’t die. Slate.

Boynton, J. (2021 March 24). Rapid Prompting Method: A New Form of Communicating? Hardly. The Skeptic

Burke, Michael. (2016, April 11). Double Talk: Syracuse University institute continues to use discredited technique with dangerous effects. The Daily Orange.

Gorman, B.J. (1998). Facilitated communication in America: Eight years and counting, 6 (3), 64. Skeptic.

Hemsley, B., Shane, H., Todd, J.T., Schlosser, R., and Lang, R. (2018, May 22). It’s time to stop exposing people to the dangers of facilitated communication. The Conversation.

Holehan, K., and Zane, T. (2020). Is there Science Behind that? Facilitated Communication. Science in Autism Treatment. 17(5)

Jarry, Jonathan. (2019, November 8). Who is Doing the Pointing When Communication is Facilitated. McGill Office for Science and Society.

Jacobson, J.W., Mulick, J.A., Schwartz, A.A. (1995, September). A history of facilitated communication: Science, pseudoscience, and antiscience. Science working group on facilitated communication. American Psychologist, 50 (9), 750-765.

Riggott, Julie (Spring/Summer 2005). Pseudoscience in Autism Treatment: Are the News and Entertainment Media Helping or Hurting? The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice. Vol. 4 (1).

Todd, J. T. (2016). Old horses in new stables: Rapid prompting, facilitated communication, science, ethics, and the history of magic, in R. Foxx & J.A. Mulick (Eds). Controversial Therapies for Autism and Intellectual Disabilities: Fad, Fashion, and Science in Professional Practice, 2nd edition, New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 372-409.

Travers, Jason C. (2020). Rapid Prompting Method is Not Consistent with Evidence-Based Reading Instruction for Students with Autism. Perspectives on Language and Literacy. 31-34. www.DyslexialDA.org

Blog Posts:

Actually there are published results for S2C/RPM…and they aren’t good

A long history of derision and embarrassments for Syracuse University’s support of FC

Another problem for FC: pseudoscientific fallacies about science

Another side effect of FC: Alternative Facts

A psychologist overlooks the science and a journalist, the full story

Critical Questions the CBS LA Reporter Apparently Forgot to Ask About FC

FC propaganda and censorship on WHYY TV

Has FC changed since the early 1990s?

Questions to ask facilitators and yourself while observing FC/S2C/RPM sessions

The Washington Post chooses a “feel-good” story over science