What Did Bernard Rimland Actually Say about ESP and Savant Skills?

Before reviewing Episode 5 of the Telepathy Tapes, I want to take a minute to talk about a claim Diane Hennacy Powell made in Episode 4 about an autism father and researcher, Bernard Rimland. Readers might remember Powell is a self-described “neuropsychiatrist” who inspired documentarian Ky Dickens to explore the topic of telepathic abilities in nonspeaking autistic individuals and create the Telepathy Tapes podcast. Rimland, Powell tells listeners, “founded an autism research center in San Diego. He evaluated thousands of children and low-and-behold in his writings he said that ESP is a savant skill.” Since coming across this information, Powell has been “working from the premise” that ESP needs to be considered a savant skill.

This man has the “savant” skill of accurately naming the day of the week when given the date on a calendar. In this case, he knew that March 1, 2044 will be a Tuesday. (From Prisoners of Silence, 1993)

For those new to this topic, according to a 2020 NIH article titled Autism Spectrum Disorder: Communication Problems in Children, repetitive or rigid language, narrow interests and exceptional abilities, uneven language development, and poor nonverbal conversation skills (e.g., limited use of gestures to give meaning to their speech) are among the patterns of language use and behaviors often found in children with ASD. In the article, “narrow interests and exceptional abilities” are defined as follows:

Some children may be able to deliver an in-depth monologue about a topic that holds their interest, even though they may not be able to carry on a two-way conversation about the same topic. Others may have musical talents or an advanced ability to count and do math calculations. Approximately 10 percent of children with ASD show “savant” skills, or extremely high abilities in specific areas such as memorization, calendar calculation, music, or math.

Note: I searched the NIH for “ESP” and “extrasensory perception,” but was unable to find any reference to either term on their website. ESP was not listed as a savant skill.

Nevertheless, Powell’s statement about Rimland and ESP did not ring true to me. I know a little bit about Bernard Rimland because of my research into FC (he supported the technique early on but then changed his mind about it when the reliably controlled studies in the U.S. were published). I also know some people who worked with Rimland, so I asked them what they thought about this statement. According to the feedback I got, Rimland was known for having some outlandish ideas about autism treatments. I get the sense that he tended to rule everything in before, systematically, ruling things out, but none of the people I contacted who knew Rimland remembered him specifically supporting ESP as a savant skill.

Book cover to Serban’s 1978 book “Cognitive Defects in the Development of Mental Illness”

While I was poking around the Telepathy Tapes website, I found a pdf to a 2015 article Powell wrote titled, “Autistics, Savants, and Psi: A Radical Theory of Mind” and, while Katharine or I could write a whole blog post about that article, today I want to focus on the reference list, which included a book published in 1978 called Cognitive Defects in the Development of Mental Illness in which there is a chapter by Bernard Rimland that Powell uses to support her claims about Rimland and ESP.

It turns out that Powell’s description was interesting, but not accurate. It is true that Rimland established an autism center called The Institute for Child Behavior Research (ICBR) in San Diego. The institute, in Rimland’s words, served as “a world registry of cases and a clearinghouse for information on autism and related disorders.” At the time Rimland wrote the book chapter, files at the ICBR contained information on over 5,400 children from the United States and 39 foreign countries. (Serban, 1978, p. 45)

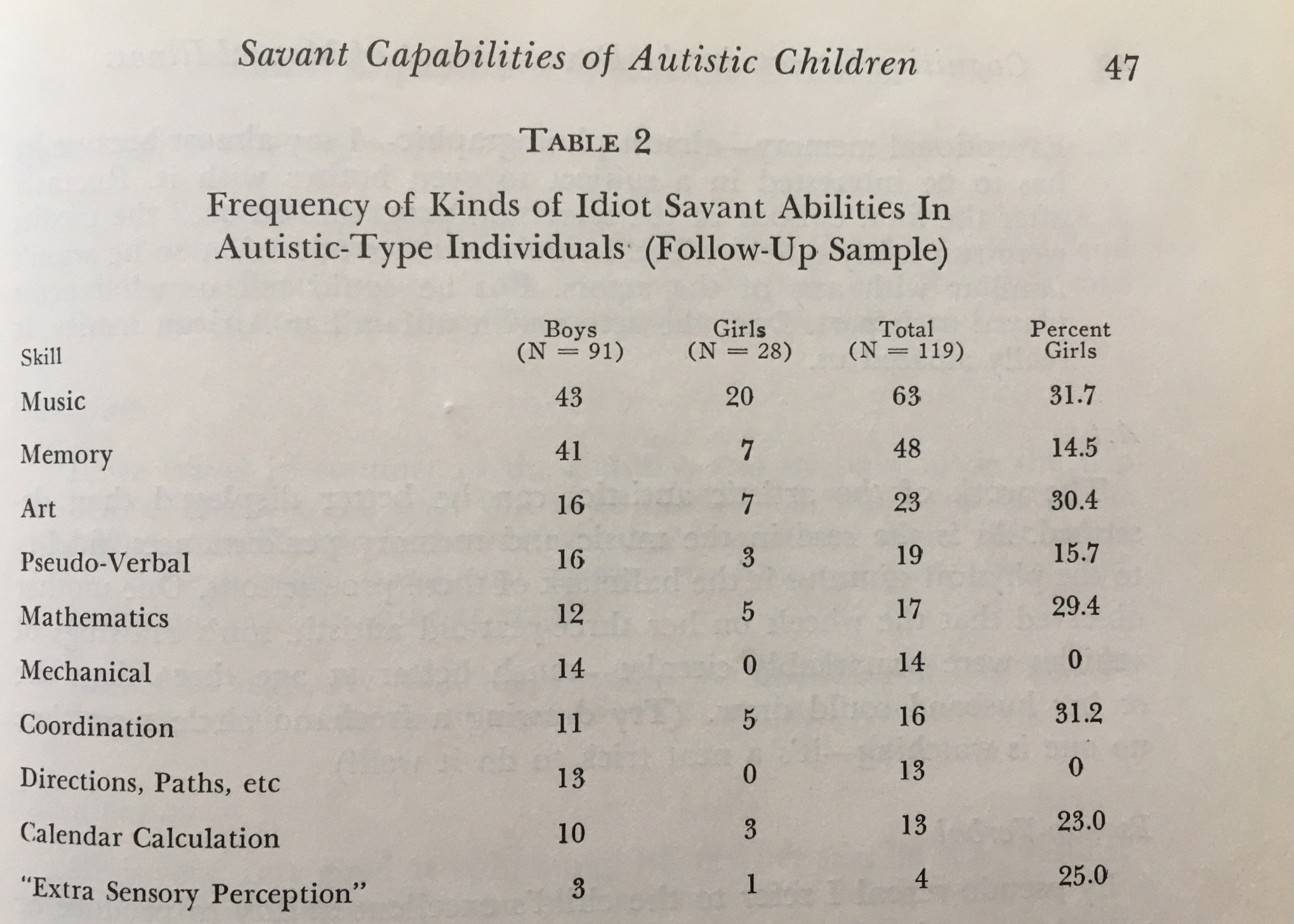

It is also true that Rimland and his staff interviewed thousands of parents using a detailed questionnaire and that this questionnaire included asking parents to describe any “special abilities” their autistic child displayed. (Serban, 1978, p.45). Rimland also mentions the work of Lewis A. Hill who published two articles that Rimland references in the chapter (please excuse the terms that were used to describe savants in the 1970s): “Idiot savants: a categorization of abilities” published in the journal Mental Retardation, and “Idiot savants: rate of incidence” published in the journal Perceptual and Motor Skills in 1977 (the article was in press at the time Rimland’s chapter was published). To gather data for his articles, Hill, according to Rimland, reached out to 300 residential facilities asking about their populations and received 111 replies. Those 111 facilities served approximately 90,000 individuals with autism and developmental disabilities. Of those 90,000, 54 individuals were reported to be savant (about .06%). This number backs up Rimland’s assertion that not all nonspeaking or minimally speaking individuals exhibit savant abilities.

As an on-going project at the institute, Rimland and his staff corresponded with the parents of children who were identified as having savant abilities. They asked the parents to give examples of their child’s special abilities, the presence of multiple abilities, the age of onset, decline of performance, if applicable, familial occurrence of related superior abilities and the like. At the time Rimland wrote the chapter, they had 119 useable replies. (Serban, 1978, p. 45). Four of the parents reported that their children had “extrasensory perception.”

Four.

It's important to note here that, in his chapter, Rimland neither supports nor refutes the presence of ESP in nonspeaking individuals with autism. The chapter merely documents parental anecdotes of the special capabilities of their children. Indeed, the parents included in Rimland’s survey reported a variety of skills involving music, memory, art, calendar calculation, etc. and the reports of ESP were, according to Rimland, “a very unexpected outcome.” (Serban, 1978, p. 49). Examples of the “extrasensory” abilities reported by the parents (paraphrased from Serban, 1978, p. 50) included:

a child, purportedly, being able to tell when his parents were going to pick him up at school, even at “random” times

a child’s ability to hear conversations out of hearing range and/or to pick up thoughts not spoken

a child’s ability to relate a story to a father about his broken watch when the child was not present when the watch fell apart. These same parents also reported several similar “clairvoyant” incidents that they were unwilling to consider coincidental.

Even though there were four responses, Rimland only gave these three examples of ESP.

Given the weight Powell puts on Rimland’s reporting of ESP as a savant skill, I was surprised to learn how little emphasis the topic gets in the chapter. As I mentioned earlier, Powell stated on the Telepathy Tapes that “low-and-behold in his writings he [Rimland] said that ESP is a savant skill.” In reading the chapter myself, I’d say that Powell is grossly exaggerating Rimland’s endorsement of ESP. For me, at least, there was no “low-and-behold” moment. Rimland’s accounts of all the supposed savant skills listed in the chapter were based on parental reports, not the direct evaluation of the children themselves. In other words, he was taking their word for it without further investigation.

And Rimland wasn’t saying ESP was a savant skill. He was saying that four of the parents who filled out the institute’s questionnaire reported their children had ESP. He was merely documenting their observations/beliefs. He also included ESP skills on a chart that listed savant skills, as reported by the parents who responded to the questionnaire. Perhaps Powell didn’t realize that anecdotes such as these are not evidence that ESP exists. Anecdotes are often the place to start the process of scientific inquiry and that is, perhaps, why Rimland was interested in documenting the parents’ stories.

Bernard Rimland’s list of savant capabilities of autistic children as reported by parents (in Serban, 1978, p. 47)

In my opinion, there was not enough information in Rimland’s chapter to confirm or deny the parents’ anecdotes of ESP in their children, though I have no doubt in the sincerity of their reporting. For me, these anecdotes—stories of ESP—lend themselves to more questions that could be explored under carefully controlled conditions and were not intended to be taken as fact. If I were Rimland or Hill or Powell, I would find these reports interesting, but would want to explore the parents’ claims in more detail. How many times, for example, did child 1 say that his parents were picking him up from school and they didn’t show up? Isn’t it possible that the teacher just remembered the times he was right and forgot or ignored the times that he wasn’t? Was child 2 truly able to hear conversations out of hearing range? What did the parents mean when they reported that their child could “pick up thoughts not spoken?” In what specific instances did this happen? And could child 3 have heard the father talk about his broken watch (either when it happened or later in the day) when the father wasn’t aware his child was within earshot? It’s quite possible (and plausible) that instances of seeming psychic abilities between children and their parents, though appearing to be unusual, mystical or magical, could have alternative, more down-to-earth explanations.

Powell said herself that she’s “working on the premise” that ESP is a savant skill and it appears that, in a sense, she is “proving” (to herself) that it is by only looking at the “evidence” that confirms her belief. If Powell read Rimland’s chapter and came away with the idea that he supported ESP as a savant skill, then I wonder about her scientific training and critical thinking skills. She seems to put so much stock in the list Rimland made that she’s based her whole career and reputation on four unexplored stories parents of autistic children shared with Rimland about what they believed to be instances of ESP.

Powell, to me anyway, doesn’t seem all that curious about finding out whether the claims being made about ESP and nonspeaking individuals with autism have alternative explanations, which is—or should be—part of the process of scientific inquiry. Neither, as we’ve seen in the first four episodes of the Telepathy Tapes, does she show any interest in exploring authorship in Facilitated Communication (FC). She seems content to take as fact that authorship in FC is free from facilitator control. (It isn’t). She ignores or downplays the fact that every facilitator featured in the Telepathy Tapes to date is providing physical, visual, or auditory cues to their clients during letter selection. The facilitators are also given access to the test stimuli (e.g., pictures, numbers, letters). She should be asking (but doesn’t) what would happen if the facilitators were not allowed to cue their clients and/or if they were not allowed to see the test stimuli (e.g., words, pictures, numbers)?

I think it’s quite possible that Powell convinced herself early on that ESP was a savant skill that autism expert Bernard Rimland believed in. This, in turn, clouded her ability to view the topic objectively and, by invoking Rimland’s name, leant an air of credibility to her hypothesis. In turn, this made it (psychologically) difficult, if not impossible, for her to question FC authorship directly. If she risks testing FC (to rule in or rule out facilitator influence) and finds out that the facilitators control letter selection, then her pet hypothesis about telepathy as a savant skill would be completely derailed.

Powell’s not the first or, I fear, the last person to be fooled into believing the illusion of FC. I don’t fault her for that. But what disappoints me about Powell is her apparent lack of interest in the existing evidence that discredits FC. If she truly wanted to be scientific about her investigation into the abilities of the nonspeaking individuals featured in the Telepathy Tapes, she would set up reliably controlled authorship tests designed to rule in or rule out facilitator control over letter selection. But, then again, blinding facilitators (and not the participants) to test stimuli might very well shatter her dearly held beliefs about ESP if she and her team proved that the nonspeaking individuals with autism being subjected to FC in her study weren’t telepathic but, instead, were being controlled (however inadvertently) by their facilitators.

References and Recommended Reading

Anonymous. (2020, April). Autism Spectrum Disorder: Communication Problems in Children. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. NIH Pub. No. 97-4315

Green, G. (1994). “Facilitated Communication - Mental Miracle or Sleight of Hand?” Skeptic Magazine.

Green, Gina; Shane, Howard C. (Fall, 1994). Science, Reason, and Facilitated Communication. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, vol. 19(3), 151-72.

Lilienfeld, S., et al. (2014). The Persistence of fad interventions in the face of negative scientific evidence: Facilitated communication for autism as a case example. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 8 (2), 62-101. DOI: 10.1080/17489539.2014.976332

Rimland, Bernard. (1978). Savant Capabilities of Autistic Children and their Cognitive Implications. In Serban, George. Cognitive Defects in the Development of Mental Illness. New Yor: Brunner/Mazel. 43-65