Whose Voice? A review of Makayla’s Voice

Largely eclipsed by the Telepathy Tapes Podcast is another documentary on non-speaking autism released at the end of 2024: a Netflix documentary short, Makayla’s Voice: A Letter to the World, first referenced here at facilitatedcommunication.org as an item on one of last year’s news roundups.

In the space of 23 minutes, Makayla’s Voice recounts the story of a 14-year-old girl whose communication skills were purportedly unlocked by a Spelling to Communicate (S2C) practitioner by the name of Roxy Sewell.

Makayla, as it’s quickly revealed, “is essentially nonverbal” and has a rare chromosomal abnormality known as 22q13 deletion syndrome, aka Phelan–McDermid syndrome (PMS). Approximately 100% of cases of 22q13 deletion syndrome involve intellectual disability and global developmental disability; at least 25% manifest as autism.

It appears quite likely that Makayla is among the 25+% of those with 22q13 deletion syndrome who also manifest as autistic. In the documentary, she shows behaviors consistent with profound autism: fleeting eye contact, self-stimulatory behaviors, and minimal spoken language ability. The documentary’s voiceover agrees. It voices “the thoughts expressed in this film,” purportedly “written entirely by her [Makayla] using a letterboard,” and introduces Makayla with these three words: “I have autism.” Nonetheless, Makayla’s most distinctive diagnosis is something other than autism, and this is one key factor that makes this documentary somewhat different from other pro-FC documentaries. The other distinguishing factor, as I’ll discuss later, is the voiceover.

It’s Makayla’s father, appearing immediately after the introductory voiceover concludes, who reveals Makayla’s “official diagnosis” to be 22q13 deletion syndrome. But from this point onwards all references to 22q13 deletion syndrome cease, and Makayla is presented simply as someone with autism. This terminological sleight of hand, which shows us yet another way in which the autism spectrum has been scrambled, allows the documentary to distance itself from intellectual disability: while close to 100% of those with 22q13 deletion syndrome are intellectually disabled, “autism” is more ambiguous. Indeed, there’s evidence that at least some minimally speaking autistic individuals, measured on certain nonverbal measures of intelligence, have close-to-normal IQ scores.

As soon as it presents itself as about “autism” rather than about 22q13 deletion syndrome, Makayla’s Voice starts to look a lot like most other pro-FC documentaries. That is, it:

waffles back and forth between autism as a curse and autism as a gift

presents autism as a mind-body disconnect

claims that society wrongly dismisses non-speakers

presents facilitated messages that reflect what people want to hear

presents facilitated messages that promote facilitated communication

includes videos and other material that unintentionally reveal the hijacking of identity and agency

Let’s consider these one by one.

1. Autism as a curse

Voiceover messages attributed to Makayla include:

All hardships erase joy. I have an example. Autism. I wish I could be more like my siblings.

We also experience so much alone, thanks to autism. (This particular message also falls into the misleading “we autistics” category I blogged about earlier).

I hope I can end silence and autism.

2. Autism as a gift

Voiceover messages attributed to Makayla include these messages about wisdom and intelligence:

I'm really smart. I process information really fast.

The deepest messages come from those who, like Van Gogh and me, communicate differently.

And from her facilitator, Roxy, who uses the word “gifts” for Makayla’s differences:

She’s tapping into a layer of herself that most of us speakers don’t have access to because we are constantly listening in order to respond to someone else, whereas Makayla's listening, and she's taking in her world, and internalizing it, and reflecting on it at this deep, deep soul level, that I feel perhaps her father has access to as an artist.

Then there is this message, attributed to Makayla, about a special connection to nature:

The most beautiful sound I have ever heard is the empty way air flows between the trees. The sound goes unnoticed by most. But to me, it sings. It creates melodies that resemble my own silence. I belong in nature… The wind is my muse, it inspires me to beam in my own way… We are the sound of hidden beauty. Winds of autism. I soar in trees.

And, besides hearing the singing of the wind, there is this message about a special musical sensibility:

It is my gift to the world to sing my silence out loud.

Finally, there are these messages about synesthesia, a common meme in the world of FC:

All my senses are heightened and I can feel emotions through them as if they are music.

I see how the autistic mind mirrors the soul in a cosmic way. It sees colors in sound. Music in the wind. My soul sees what others cannot. Truth, honesty and love are colors surrounding the heart. I literally see that. It's music.

3. Autism as a mind-body disconnect

Rather than messages that reflect the social challenges and intense, narrow focuses of autism—core autism characteristics that track with eight decades of diagnostic criteria, screening tools, and psychological research—we have, in the voiceover messages attributed to Makayla:

I am trapped inside my body.

I run when my body separates from my mind.

It really confuses me how my body creates so much trouble for me.

Consistent with this, Roxy, the S2C facilitator, provides the usual explanation for how S2C is supposed to work:

When a student is first learning how to use the letter boards, they might need a lot of assistance, a lot of prompts. There's a motor piece where it's Makayla using her body to literally get every single letter on the letter board. And so that motor piece is something that's pretty exhausting.

And she describes the initial S2C lessons—which for some reason often seem to be about astronomy—as not being about academic content, which the facilitated person is presumed to have already somehow sponged up. Rather, the lessons purportedly address the motor skills of pointing to the correct letters:

In the beginning, with Makayla, we would do lessons, and I would ask her, “Today we're learning about galaxies. Let's spell galaxies.” And it wasn't that I was quizzing her on how to spell galaxies. I was helping her become confident in her body and pointing to the letters accurately.

4. Claims that society wrongly dismisses non-speakers

Some of the messages attributed to Makayla include the usual straw men about society’s supposed attitudes:

For speaking people, language is only worthy it they’re spoken by someone with speech.

In my silence I’ve learned that many assume that silence equals dumb.

5. Facilitated messages that reflect what people want to hear

Voiceover messages attributed to Makayla include messages of love and reassurance to her parents:

I love you mom. (The conclusion of a long message to her mother).

Happy late Father’s day… I love you so much it is unreal. I am so lucky to be your daughter. I get so happy to be near you… I giggle and cheer because I don’t want to allow you to ever doubt your worth. Daddio, you gave me so much, limelight, music, and love. You found my voice before anyone else did. A lot of my strength comes from the way I see you work. You are the best. I love you dad. (A message to her father, apparently shortly after being unlocked by S2C.)

We also hear messages about how intelligent she is. He father reports her as telling him:

I'm really smart. I process information really fast. I'm different but I'm here.

And the message to her mother includes:

I'm super, super smart. I learn by listening. My mind is a sponge that drinks knowledge like it's juice.

Besides these, there are the messages about Makayla’s unusual gifts—the connection to nature and the synesthesia. And from Roxy, the S2C practitioner, we hear about how creative Makayla is. Roxy illustrates this through a poem that she, Roxy, facilitated out of Makayla: a poem that, according to Roxy (the likely unwitting author), is "the most beautiful piece of writing I've ever heard.” Making comparisons between Makayla and an unloved snake, it includes words like “unworthy,” “misjudgment,” “nocturnal,” and “discreetly”—words well beyond the active vocabularies of many typical 14-year-olds. A later message facilitated out by Roxy states that Makayla wants to be an author.

6. Facilitated messages that promote facilitated communication

Like so many other FC-generated messages, Makayla’s S2C-generated messages promote FC (S2C in particular) both for herself and for others:

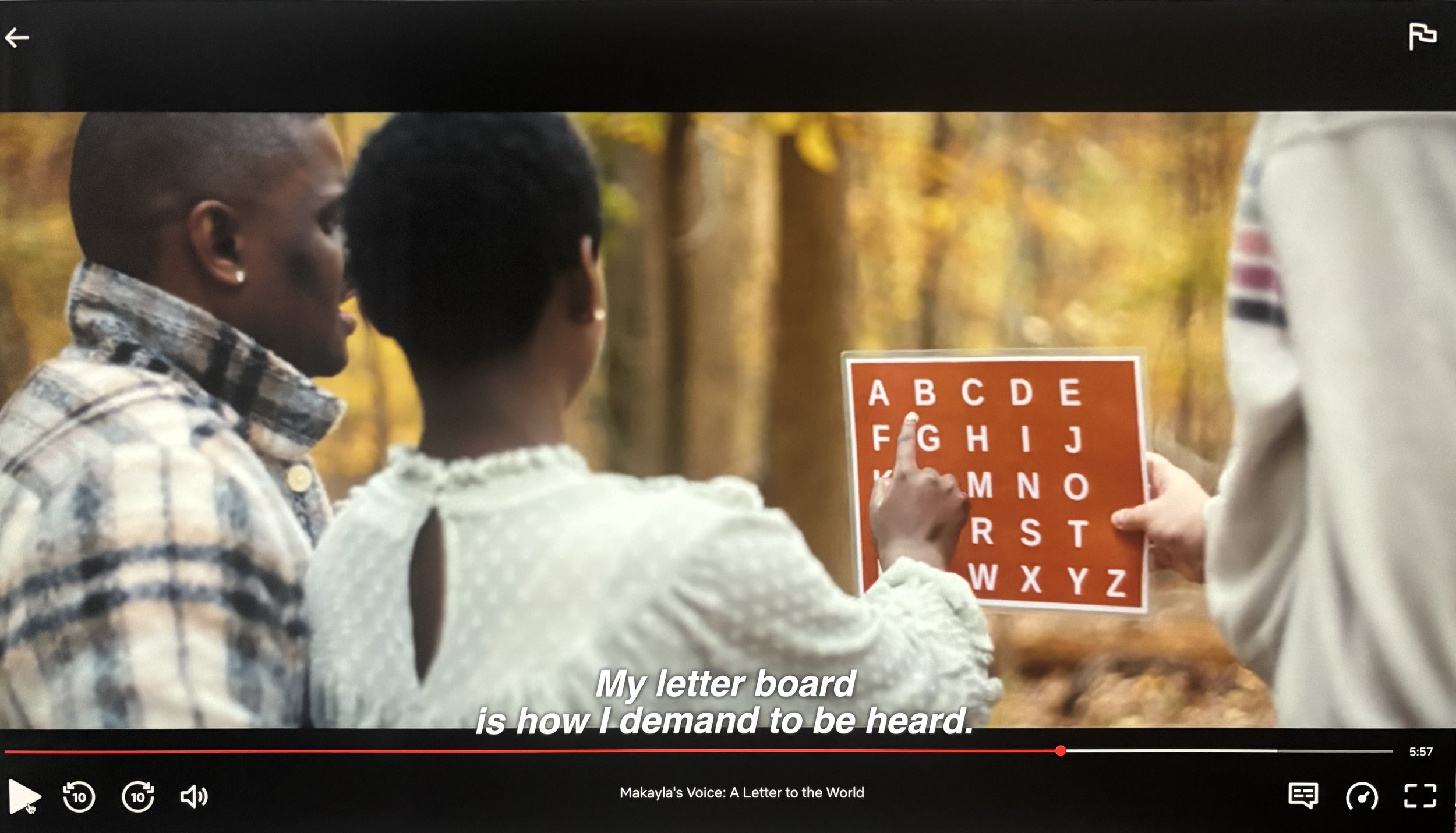

My letterboard is how I demand to be heard.

I know I’m lucky that you and Dad found Roxy so I could do this. All I had dreamt about in all my dreams really is doing this.

I hope to… change hearts. I want to show these boards to the world. Be an advocate for autistic people without a voice. I think my father can help since he knows so many people.

7. Videos and other material that unintentionally reveal the hijacking of identity and agency

In all the scenes of S2C-generated typing in which we hear the ambient noise, as opposed to the musical soundtrack, that noise includes constant verbal cueing from Roxy, the S2C facilitator, as Makayla’s finger wanders around the letterboard:

“Reach,” “You got it,” “Mm hmm,” “I got you,” “One more,” “There you go,” “Right on it,” and even—when Makayla’s about to hit the wrong letter—“Don’t put it down until you get to your letter,” and, when Makayla’s index finger gets there, “There.”

In the course of facilitating the word “Mexico,” Roxy cues "Right on it" twice after Makayla’s index finger hits several letters between the “X” and the “I”; she then cues “Right on it” a second time when Makayla points to another extra letter between the “C” and the “O”. Roxy then pulls the board away even though Makayla is still pointing.

In the course of facilitating the word “Russian,” when Makayla types “R-S-S-I” (without the “U”), Roxy cues “Reach,” Makayla hits another letter, and then Roxxy then calls out the word “Russian.” (Roxy then exclaims, laughing, “That's not what I thought she was going to say!”)

When Makayla’s father starts to ask "Why are you so resistant to getting in the pool at the beginning?" Makayla clearly wants to start pointing at the board before he finishes the question, and indeed does just that—before it’s clear what her father is even asking her. The letters she ends up hitting, as called out by Roxy, are “T-S-M-Y-L,” which is interpreted by Roxy as “It’s my style”.

For more on Roxy’s influence over Makayla’s letter selections, see Janyce’s video analysis here.

Throughout the entire message-generation process, Roxy is the one who controls the letterboard, even when Makayla attempts to grab it:

Roxy holds the board before Makayla starts typing:

Roxy holds the board after Makayla finishes typing:

Roxy holds the board when she has decided that Makayla’s finished, even when Makayla still has her index finger out, ready to keep pointing:

And at one point, when facilitating the word “silent,” Roxy pulls the board away after calling out the “S” and the “I”:

(Whereupon she “resets” the letterboard on front of Makayla’s index finger.)

There’s also a short clip of Roxy holding Makayla’s hand while Makayla holds a pen, causing Makayla to transcribe letters she’s first touched on the letterboard.

Throughout the documentary, we see Makayla’s near complete dependence on Roxy when producing messages. Only once do we see her holding a communication device (very briefly) on her own, and only once do we see someone other than Roxy holding the letterboard for her (very briefly, her father). In neither instance does the voiceover, or anyone else, tell us what messages, if any, Makayla is producing. Every other time she’s with her father or other family members, it’s a facilitator (either Roxy or another, unnamed facilitator) who holds up the board.

But it’s not just the S2C facilitators who exert control over Makayla’s purported communications and, indeed, her very identity. There‘s also the documentary itself: its voiceover and visuals. Not only does the voiceover read out Makayla’s purported FCed messages as if they’re authentically hers; it does so in an unusually authentic voice. That voice is purportedly selected by Makayla herself from at least three candidates. This conceit plays out the very beginning of the documentary, when two other voices read out the first message attributed to Makayla (”The most beautiful sound I have ever heard is the empty way air flows between the trees.”), and each one is dismissed (by another voice, probably Roxy’s, which says, “No. Ok, let’s try the next one”). Then a third voice chimes in, passes muster, and provides the voiceover for the rest of the documentary. That voice is provided by a voiceover artist aptly named Portia Cue.

Portia Cue’s voiceover is extraordinarily convincing. Most FCed messages are voiced by the same speech synthesizers used by text-to-speech apps, automatic checkout counters, and/or navigation apps, which makes them tougher to project onto the personalities of FCed humans. Portia Cue’s voice, by contrast, is highly expressive and authentic. Her delivery sounds spontaneous; her inflections resemble those of an adolescent girl. This makes it easy for us listeners to think of this voice, however subconsciously, as actually belonging to Makayla. The implicit theme of “Makayla’s Voice”—that of Makayla having found her voice—only adds to this illusion.

That said, towards the end, the documentary briefly undoes this notion with another message. Though voiced by Portia Cue, it states “But I want to use my real voice now.” The next scene, accordingly, shows Roxy prompting Makayla to actually speak. “What can you tell Dad?” she asks Makayla. With Roxy’s affirmation after each prompt, Makayla voices approximations of “I,” “love,” and “you.” What these word approximations mean to Makayla remains unclear. Equally unclear is what they mean about whether Makayla—unlike pretty much all other FCed individuals—is now going to move beyond the letterboard into speech. Equally unclear is whether a speech-language therapist has ever attempted to help Makayla develop her speech skills, and (given that she has some rudimental speech skills) why this appears to have been abandoned in favor of S2C.

Practically speaking, of course, Makayla cannot rely on Portia Cue’s voice. That’s because Portia Cue, unlike a text-to-speech app, cannot follow Makayla around for all her waking hours for the rest of her life. Portia Cue’s voiceover, presumably, begins and ends with the documentary. Out in the real world, in the absence of effective speech-language therapy, and using a letterboard rather than a digital device, the only voice that Makayla appears to have, at least for now, is that of Roxy (or the other, unnamed facilitator) reading aloud the messages produced by the facilitated letter selections. This, indeed, is precisely what happens in the final scene of the movie. But, presumably, this isn’t what we’re supposed to think that Makayla means by “my real voice.”

Returning to the illusion provided by the voiceover, this illusion is enhanced by a musical soundtrack that accompanies most of Portia Cue’s words. In combination with the allusions that some of those words make to Makayla’s musical sensitivities, it’s easy to hear the music as a sort of transcript of what’s going on in Makayla’s head, and also as what one of the voiceover messages, “This is my song,” refers to. So, too, with some of the documentary’s visuals, especially the images of celestial phenomena that accompany the voiceover messages about synesthesia and special connections to nature.

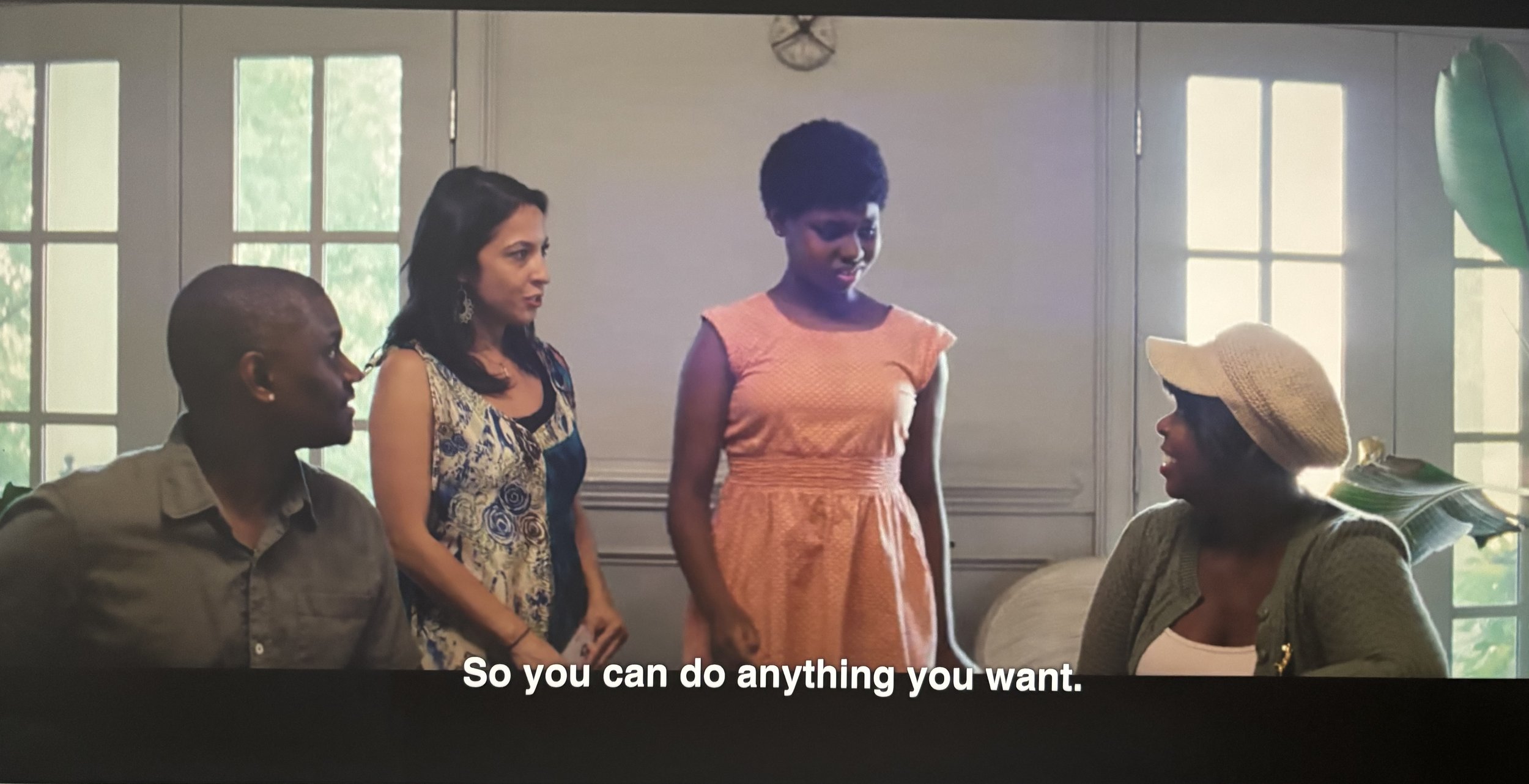

Beyond the facilitators’ control over Makayla’s messages, and the influences of the voiceover, musical soundtrack, and celestial visuals over viewers’ impressions of who Makayla is, we witness other sort of control. This is the physical control of Makayla that surfaces in the final scene. Makayla is sitting at a table with her family members, Roxy hovering above her with the letterboard in her hands (it’s the same scene as that shown in the above images of Roxy controlling the letterboard). When Makayla stands up to leave the room—presumably tired of sitting and pointing at the board—her family members tell her “Good job!” and “I’m so proud of you,” and Roxy tells her: “So you can do anything you want.”

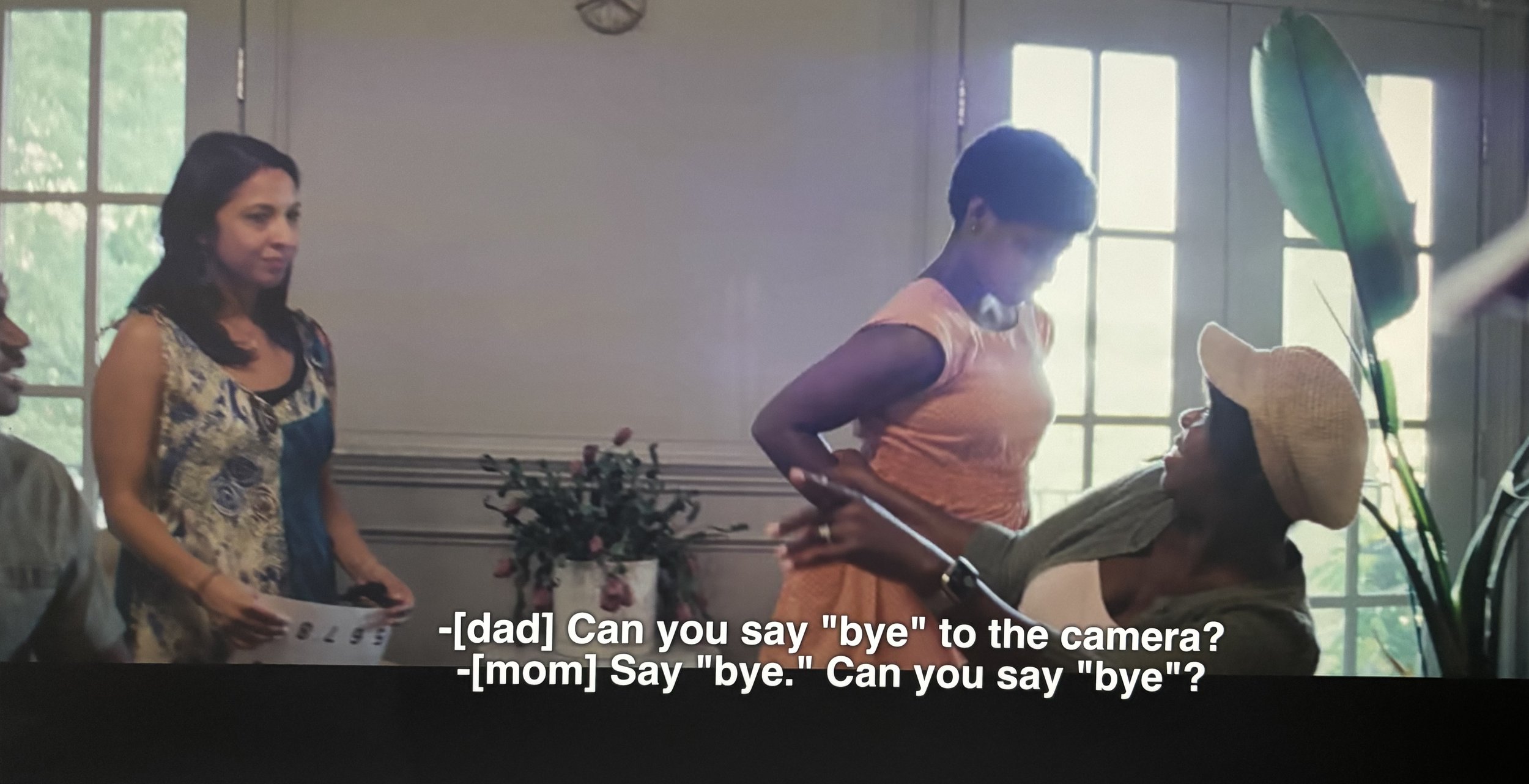

But then, as she tries to leave the room, the 14-year-old Makaya is physically pulled back and prompted by both parents to say “bye” to the camera.

Makayla complies, twice. In what may possibly be the most authentic message of the entire documentary, she quietly approximates the word; prompted to say it again louder, she approximates it again.

“Ba.”

(“Bye.”)

Now, perhaps, Makayla can do anything she wants, or at least be herself—at least for bit, until the letterboard catches up with her to extract, yet again, what the documentary wants us believe is “Makayla’s Voice.”