Scrambling the spectrum, flattening the curve, and making FC seem more plausible

A commenter recently asked:

has a word cloud analysis ever been conducted comparing the word choices and themes of FC generated communication to the natural language of higher functioning autistic people of the same age group?

I replied that I was unaware of any such analysis, but that it certainly would be interesting. Anecdotally, FCed individuals write things like:

My brain is trapped inside my body.

and

Thank you mom and dad for putting up with me all these years.

Others whose autism is somewhat more moderate write things like:

Fish in jar.

and

I want fan on fast.

Comparing a broad corpus of FC-generated communications with a broad corpus of independently-generated communications by higher-functioning autistic people of the same age might reveal more about this pattern: the pattern, that is, of more profoundly autistic people purportedly producing prose that is more sophisticated than that produced by their less profoundly autistic counterparts.

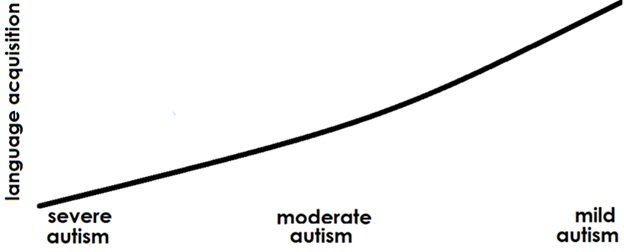

It would also provide one more reason to believe what all the available evidence strongly suggests: that all FC-generated messages (including those generated by recent variants of FC like RPM and S2C) are authored by the facilitators, not the individuals with autism. That’s because most of the research measuring autism severity and language skills finds a tight correlation between autism severity and language acquisition difficulties—as in this schematic:

The relationship to autism severity is especially tight with receptive language, or comprehension. Expressive language, or speaking and writing, depends on other factors as well (nonverbal IQ and speech-motor skills). But expressive language depends most and most essentially on receptive language: to express yourself properly, you need to know the meanings of the words/phrases/sentences you’re using.

The reason for the connection between language and autism severity has to do with one of the two basic symptom categories of autism: social deficits (the other symptom category being restrictive, repetitive behaviors). The sub-component of the social deficits most relevant to language acquisition is joint attention, specifically attending to what the people around you are looking at or pointing out to you. A host of articles (see references below) finds that reduced joint attention leads to reduced word learning. Given that a child needs to tune into what other people are saying and referring to in order to learn what new words mean, this is hardly surprising. (See also my earlier post on this question).

Thus non-speakers and minimal speakers tend to be severely autistic.

But here’s the rub. Non-speakers and minimal speakers are also much more likely than their more talkative counterparts to be subjected to FC or its variants (RPM/S2C). And those who promote FC/RPM/S2C claim that FCed individuals have sophisticated language skills that are unlocked by FC. Nor do FC proponents stop there: most go further, claiming that all non-to-minimal speakers, whether or not they’ve been subjected to FC, have sophisticated language skills that can be unlocked by FC. And if that’s the case, the above graph would have to be adjusted as follows:

Of course, one of these two graphs is a good deal more plausible than the other. But both of them depend on there being a clear scale of autism severity. And herein lies the next rub.

You’d think that autism severity would be a straightforward function of how strong a person’s core symptoms are in the two key symptom categories—social deficits and restrictive repetitive behaviors (categories A and B of the DSM criteria). But recent developments have conspired to obscure such a straightforward function. They are:

Changes to the DSM criteria for autism that affect how clearly these criteria delineate mild autism and measure autism severity.

Reinterpretation or dismissal of the DSM severity criteria by some autism spokespeople.

The publication of a new definition of profound autism that makes no reference to the core symptoms of autism.

Changes to the use of the ADOS, the gold standard for diagnosing both autism and autism severity, that make severity differences less apparent.

Claims that autistic people can hide, or “mask,” the core symptoms—particularly the social ones—so that you can’t tell how severely autistic a person is by observing their behavior.

Changes in what some advocates say autism is, de-emphasizing or dismissing what has been understood for the last eight decades to be its core symptoms.

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

1. Changes to the DSM criteria for autism that affect how clearly they delineate mild autism and measure autism severity

In 2013 the latest version of the DSM, the DSM-5, made two changes to its diagnostic criteria for autism that have rendered it less transparent in terms of autism severity. First, it got rid of the separate category of Aspergers Syndrome—until then the diagnosis for individuals with mild autistic traits and fluent language. Now everyone with autistic traits—social deficits and restrictive/repetitive behaviors—gets a single “autism spectrum disorder” diagnosis, from the verbally fluent, socially awkward college student with an all-consuming passion for electronic circuitry, to the non-speaking person who prefers Barney videos, rarely makes eye contact or interacts with others, and remains in autistic support and life skills classrooms through the age of 21.

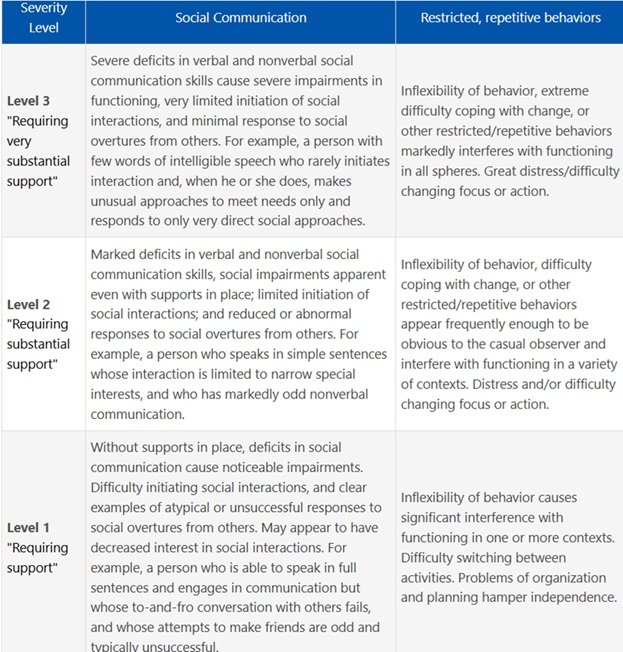

The second DSM-5 change was to supplant the informal terms “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe,” used to describe where someone is along the spectrum, with a triad of more discrete sounding “severity levels.” These levels, if you read the fine print, are supposed to reflect the core symptoms:

https://iacc.hhs.gov/about-iacc/subcommittees/resources/dsm5-diagnostic-criteria.shtml

And, accordingly, many informational websites (Autism Speaks, Very Well Health, Nexus Health Systems, The Place for Children With Autism) accurately characterize the three levels as reflecting the core social and restrictive/repetitive behaviors of autism.

However, since these levels are also cast in terms of support needs (see the first column on the chart above), they are easily misinterpreted as being less about core symptoms and more about practical needs.

2. Reinterpretation or dismissal of the DSM severity criteria by some autism spokespeople

Some autism spokespeople have, indeed, broadened the support needs that the DSM-5 has linked to autism severity to include needs relating to executive function, impulsivity, emotional regulation, or anxiety—and to needs relating to daily life activities. As one autistic YouTuber puts it:

They may be able to communicate, but cannot actually cook for themselves… There are so many reasons why a person might be high support needs but also high in communication.

Some individuals go so far as to identify themselves as Level 3 autistics despite the communication skills they use to tell us this—see here, here, here, and here.

This expansion of “ support needs” to needs that are not specific to autism can result in a fully fluent socially awkward person who once would have had a diagnosis of Aspergers being cast as someone with Level 3 autism—the same diagnosis as an autistic non-speaker who rarely engages in even the most basic of social exchanges.

From here, some autistic advocates go on to question whether the levels make any meaningful distinctions between different autistic individuals, proposing that high support needs can be present in individuals across the spectrum and that specific levels of need vary more based on the current circumstances than on the particular person. Ann Memmott, for example, writes:

If something very unexpected happens, during sensory overload, I’m back to not being able to speak, and rocking, and flapping, and maybe running away. If a diagnostic person tried to interview me during that, they might think, “Level 3.”

…

Autism is a dynamic thing. Our sensory and routine-based needs vary according to age, and how exhausted we are, whether we are in pain, whether we are comfortable with those around us. They vary according to our sensory environment, how well we are able to plan ahead from the information given to us. They vary according to background situations such as depression, anxiety, trauma. How are we picking a day on which to award a “level,” and declaring that’s a fixed thing for life?

And Amythest Schaber a YouTuber who likewise identifies as autistic, talks about how, depending on the circumstances, a verbal autistic person can become non-verbal after “going through burnout.” She explains how she will “go nonverbal” when she’s “close to meltdown,” and how daily living activities become difficult for her “after burnout,” and how she wouldn’t be capable of living on her own because she might forget to eat, drink, go to the bathroom, or clean herself.

3. The publication of a new definition of profound autism that makes no reference to the core symptoms

In 2022, the Lancet Commission published an article on the future of care and clinical research in autism, with Catherine Lord as lead author, that proposed criteria for what it calls “profound autism”—a term used interchangeably with “severe autism.” Its criteria for profound autism are:

requiring 24 h access to an adult who can care for them if concerns arise, being unable to be left completely alone in a residence, and not being able to take care of basic daily adaptive needs.

The article adds that:

In most cases, these needs will be associated with a substantial intellectual disability (eg, an intelligence quotient below 50), very limited language (eg, limited ability to communicate to a stranger using comprehensible sentences), or both.

In other words:

To represent the intensity of needs in a standard manner, profound autism is thus defined not by autistic features but by intellectual or language disability.

Under the guidance of Dr. Lord, the Child Mind Institute, has followed suit:

Profound autism is defined as having an IQ of less than 50 or being nonverbal or minimally verbal. Kids with profound autism need help with tasks of daily living, such as dressing, bathing, and preparing meals. They are also likely to have medical issues like epilepsy and behaviors like self-injury and aggression that interfere with safety and well-being. They require round-the-clock support, throughout their lives, to be safe.

While this definition makes sense from a practical standpoint—mapping profoundly autistic individuals to their intensive needs—it has the downside of failing to distinguish autism from the many other conditions that drastically affect language and cognition and that also require round the clock care, e.g., major genetic disorders like FOXG1 Syndrome, and many cases of cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, and Williams Syndrome. And, of course, the Lancet’s criteria for profound autism has the above-discussed downside of creating a loophole in which verbal people with normal cognitive ability can be considered profoundly autistic—provided they’re incapable, as Amythest Schaber has said of herself, of living on their own.

Nor is it actually necessary to redefine profound autism this way. Severe social deficits and severe rigidity, with their severe effects on language acquisition and adaptive functioning, are enough to result in a need for 24-hour care and supervision—regardless, even, of IQ level (as one study finds, when measured on non-verbal cognitive assessments, some profoundly autistic minimal speakers show relatively intact cognitive skills).

4. Changes to the use of the ADOS, the gold standard for diagnosing both autism and autism severity, that make severity differences less apparent

The reason the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, or ADOS, is considered the gold standard for diagnosing autism and measuring autism severity, is that it:

measures core symptoms—both social deficits and restrictive repetitive behaviors, and

does so by direct, structured observations of the child in specific, standardized, structured contexts.

In the last decade, however, the ADOS has been partially supplanted by a “calibrated ADOS” that is, effectively, less sensitive to autism severity.

That’s because this calibrated ADOS, unlike the original, controls for language. As its designers (Gotham et al., 2008) explain:

Calibrated severity scores do not measure functional impairment, but are intended to provide a marker of severity of autism symptoms relative to age and language level.

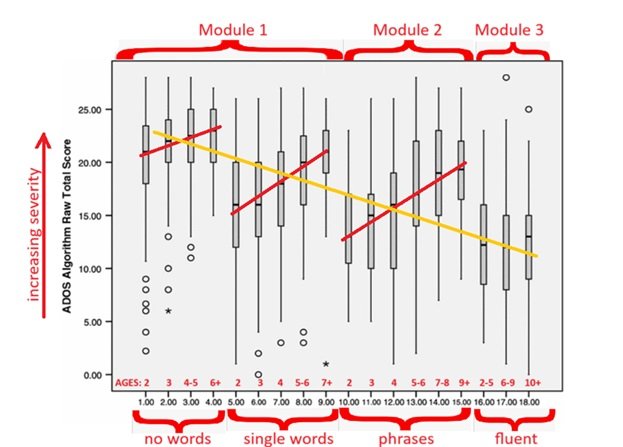

Motivating this adjustment is the fact that the ADOS, when used with children, is divided into three distinct testing modules, with different children assigned to different modules. Which module a child is assigned to depends on their language level. Module 1 is for those with no words or only single words; Module 2, for those with phrase speech; and Module 3, for those with fluent language. The ADOS makes these distinct assignments because the assessment activities used in the different modules depend to some extent on language level. Module 1 has no activities requiring verbal responses, while Module 2 includes “Description of a picture,” “Conversation,” and “Telling a story from a book,” and Module 3 adds “reporting” and “Creating a story.”

Controlling for language, then, potentially makes it easier to compare the scores obtained by children who were tested in different modules that vary according to their language-based activities—or lack thereof.

But controlling the ADOS’s autism severity measures for language also has two drastic effects:

It obscures the connection between language and severity discussed at the beginning of this post.

It flattens the differences in symptom severity across the autism spectrum.

To see this, let’s compare two graphs of ADOS scores from a sample of 1,415 children across the spectrum. Here is an annotated graph that shows the original ADOS scores, grouped by module, language level, and age.

In this original ADOS graph, where raw scores range from 0 (no symptoms) to 28 (most severe), you can see, in the downward-sloping yellow line, big differences in autism severity across the spectrum. More specifically, you see mean autism symptomology scores (see the vertical axis) in each of the four groupings of the age/language levels ranging (see the red brackets along the horizontal axis) from about 23 (severe) down to about 13 (mild). You can also see how the ADOS severity scores correlate with how much language a person has: with no words and single words correlating with higher ADOS scores, and phrase and fluent language correlating with lower ADOS scores. Finally, you can also see how, within the no words, single words, and phrase groups, raw ADOS scores correlate with age: the older a child is when he or she is still in one of the more limited language groups, the more severe his/he autism symptoms (see the three upward-sloping red lines). Thus, with the original ADOS, autism severity varies significantly across the spectrum and correlates tightly with language.

In the calibrated ADOS, which controls for language, all of these factors are automatically dampened. The 0-28 point raw scores of the original ADOS are mapped onto a 10 point scale, and the differences between language groups are flattened (see the flatter yellow line), as are the correlations between the age at which a child is still within a given limited language group and the severity of his or her symptoms (see the flatter red lines).

Interestingly, the authors acknowledge that ADOS scores still rise somewhat with the age of a child within a given language group. But they blame this on IQ deficits rather than social deficits, stating that “This apparent age effect seems likely to be explained by lower verbal IQ in the older children without fluent speech.” Thus, once again, something other than core autism symptomology is invoked to explain autism severity.

5. Claims that people can hide, or “mask”, the core symptoms—particularly the social ones—so that you can’t tell how severely autistic a person is by their behavior

Another phenomenon that effectively suppresses the role of core symptomology in autism severity is the notion that autistic people can “pass” as socially normal by “masking” their social differences—a practice attested to by a number of YouTubers who identify as autistic (see here, here, and here). The implication is that someone can look socially normal but actually be more than just mildly autistic.

But the ability to mask, defined as something that autistic people do to fit in with their neurotypical peers, requires (1) strong social motivation and (2) an awareness of what counts as socially normal, both of which are specific to mild autism and completely absent in severe autism.

6. Changes in what some advocates think autism is, de-emphasizing or dismissing what are understood to be the core symptoms.

Building on the idea of masking is a new article out of UC Santa Barbara entitled “In a paradigm shift for autism, practitioners move beyond traditional demographics and toward adaptive environments.” It cites Anna Krasno, clinical director of UC Santa Barbara’s Koegel Autism Center as rejecting the ADOS, calibrated or uncalibrated, as overly focused on social deficits:

Traditional diagnostic tools like the widely used Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Krasno explained, are rooted in outdated notions of autism. These tools often fail to account for traits like masking or sensory sensitivities, particularly in verbal individuals or adults. “We’re advocating for a broader, more inclusive approach that includes self-report measures and considers cultural and gender diversity,” she said.

Not surprisingly, the first of Krasno’s suggestions for making workplaces and institutions more autism-friendly are noise-canceling headphones. Many other autistic self-advocates have likewise re-analyzed autism as a sensory disorder; some rate themselves as at least as socially motivated as their non-autistic peers (see Mournet et al., 2023).

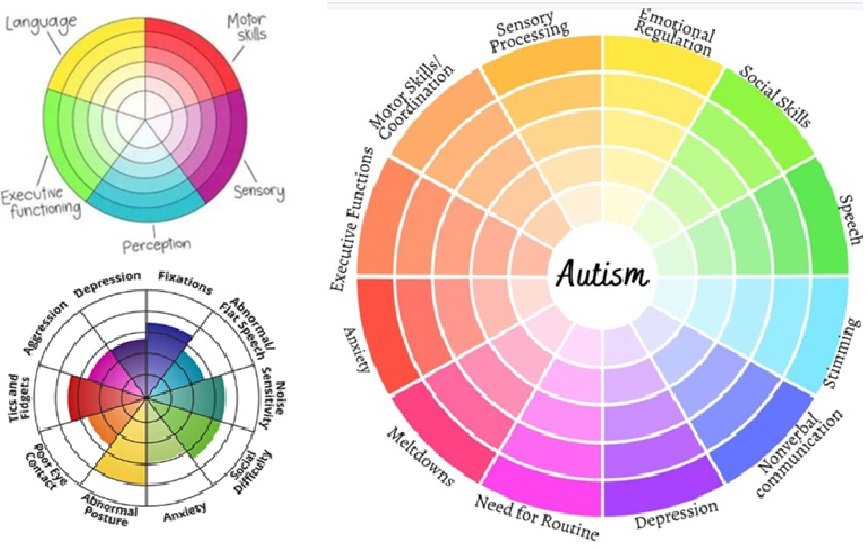

Reflecting all this is what you find when you look up “autism spectrum” on Google Images. Crowding out the traditional linear images that run from severe to mild, defined in terms of the two symptom categories, social impairment and rigid/repetitive behaviors, are circular images like these, in which the roles of the core symptoms are drastically reduced or eliminated to make room for many other non-core, non-autism-specific traits:

For eight decades, the clinical definition of autism has held steady. To this day, an autism diagnosis requires significant social deficits and rigid repetitive behaviors. Everything else—meltdowns, anxiety, sensory processing issues, motor skills challenges, challenges with executive functioning, challenges with emotional regulation—while often co-occuring with autism, is optional. There are plenty of autistic people who lack one or more of these peripheral conditions; but no one, properly diagnosed with autism, lacks the core social and rigid/repetitive features of autism that date back 8 decades to Leo Kanner, the guy who first delineated autism as a developmental disorder.

How is all this relevant to FC?

Most obviously relevant to FC is the reanalysis of autism as something other than a social disorder. This dates back to early FC proponents like Douglas Bicklen and continues on with 21st century FC proponents like Vikram Jaswal: believing in FC/RPM/S2C means believing autism is instead some sort of motor disorder (see Biklen, 1990; Jaswal & Akhtar, 2019).

More generally, the more we try to will away the existence of severe autism and the degree to which autism severity is a function of social deficits, the more we can obscure one key reason why FC is so implausible: more severely autistic kids somehow being so much more verbally expressive in their written language than their less severely autistic counterparts.

That is, the implausibility of:

"When we relate a truth or a perception to some known field through metaphors, it becomes the stepping stone towards better cognition. (Reportedly typed by a profoundly autistic, facilitated young man.)

vs.

I want daddy car. (Typed by a less profoundly autistic, unfacilitated young man).

And the implausibility of:

GENERAL REFERENCES

Biklen, D., (1990). Communication Unbound: Autism and Praxis. Harvard Educational Review 60(3), 291–315.https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.60.3.013h5022862vu732

Courchesne, V., Meilleur, A. A., Poulin-Lord, M. P., Dawson, M., & Soulières, I. (2015). Autistic children at risk of being underestimated: school-based pilot study of a strength-informed assessment. Molecular autism, 6, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-015-0006-3

Gotham, K., Pickles, A., & Lord, C. (2009). Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 39(5), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3

Jaswal, V. K., & Akhtar, N. (2019). Being versus appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 42, e82. doi:10.1017/S0140525X18001826

Lord et al., 2022. The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. The Lancet, 399(10321), pp. 271-334.

Mournet, A., Bal, V., Selby, E. A., & Kleiman, E. (2023, February 27). Assessment of multiple facets of social connection among autistic and non-autistic adults: Development of the Connections With Others Scales. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/d6t5k

REFERENCES LINKING JOINT ATTENTION AND AUTISM SEVERITY TO RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE

Charman, T., Baron-Cohen, S., Swettenham, J., Baird, G., Drew, A., & Cox, A. (2003). Predicting language outcome in infants with autism and pervasive developmental disorder. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 38(3), 265–285. doi:10.1080/136820310000104830 PMID:12851079 (Joint attention predicts language learning.)

Sigman, M., & McGovern, C. W. (2005). Improvement in cognitive and language skills from preschool to adolescence in autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 35(1), 15-23. (Joint attention predicts language learning.)

Charman, T. (2003). Why is joint attention a pivotal skill in autism?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358(1430), 315-324 (Joint attention predicts language learning.)

Ellis Weismer, S., & Kover, S. T. (2015). Preschool language variation, growth, and predictors in children on the autism spectrum. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 56(12), 1327–1337. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12406 (“ASD severity was a significant predictor of growth in both language comprehension and production during the preschool period.”)

Luyster, R. J., Kadlec, M. B., Carter, A., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2008). Language assessment and development in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(8), 1426-1438. (Links joint attention and nonverbal cognitive ability to language development.)

Peters-Scheffer, Nienke & Didden, Robert & Korzilius, Hubert & Verhoeven, Ludo. (2018). Understanding of Intentions in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2. 10.1007/s41252-017-0052-2. (Finds “a relation between the understanding of intentions and early social communication and language.”)

Thurm, A., Lord, C., Lee, L. C., & Newschaffer, C. (2007). Predictors of language acquisition in preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1721–1734. doi:10.100710803-006-0300-1 PMID:17180717 (Early joint attention is more impaired in children who, despite having relatively high nonverbal cognitive skills, do not develop language by age five than it is in those who do.)

Yoder, P., Watson, L. R., & Lambert, W. (2015). Value-added predictors of expressive and receptive language growth in initially nonverbal preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 45(5), 1254-1270. (Autism severity predicts language delays.)