Do facilitated individuals have motor difficulties that explain away our concerns about FC? Part I

Ever since Douglas Biklen began promoting facilitated communication in the 1990s, one of his central claims—and one of the central claims of other FC proponents—has been that autistic individuals have difficulty controlling their bodies. This, purportedly, includes difficulties with motor control and motor planning (e.g., with ten-finger typing) and with what I’ll call “intentional control”: the ability to inhibit one’s body from carrying out an unintended goal (e.g., inhibiting the urge to flap one’s hands or echo a favorite phrase) that would interfere with an intended goal (e.g., intentional communication).

The term “intentional control”, I should note, is my own coinage. It’s a workaround for the fact that proponents haven’t given us a precise term for the phenomenon in question. Sometimes they call it “praxis”—and then use “apraxia” for significantly impaired “praxis”. But, outside the FC world, “praxis” is consistently defined as motor planning: planning out a combination or series of motor movements. And, outside the FC world, “apraxia”—whether speech apraxia (difficulty making intended speech sounds), oromotor apraxia (difficulty with other oral movements like chewing and swallowing), or more general apraxia (difficulty performing intended or requested motor sequences like cutting out a requested shape)—is consistently defined as a significant difficulty with motor planning. That is, praxis/apraxia apply to situations where what’s at issue is whether someone has the motor planning skills to accurately carry out certain physical goals/commands (e.g., cutting out a triangle or saying the word “lickety-split”). Praxis/apraxia do not apply when what’s at issue is whether someone can inhibit other physical goals/urges (e.g., flapping their hands or echoing the word “popcorn”) that interfere with their primary goal (e.g., saying “thank you”).

So how does FC fit into all this?

The story goes as follows. Motor control difficulties are supposed to explain the inability to speak, the inability to type with ten fingers, and the need to have another person hold one’s wrist or elbow in order to keep one’s typing arm/index finger steady. Intentional control difficulties, meanwhile, are supposed to explain the fact that an autistic person’s spoken words or behavior are often at odds with what they type when subjected to facilitation. Think of the S2Ced person who says “No more! No more!” while typing about her feelings towards another person, or the RPMed person who, when asked what he wants for breakfast, refuses pancakes after he types pancakes.

Finally, some combination of motor control difficulties and intentional control difficulties are supposed to explain why the cognitive skills and language comprehension skills of facilitated individuals, as assessed in formal, unfacilitated settings, appear to be so much lower than the cognitive and linguistic levels displayed in their facilitated output. Think of the S2Ced individual who, when asked by an S2C professional what field alchemy turned into, can type “chemistry” onto a held-up letterboard , but who, when asked during a cognitive assessment to point to a green object, points to a red object instead.

So what is the evidence for motor control and intentional control challenges in autism? What is the evidence that autism is, as Biklen and others put it, a motor disorder, and not, as the DSM defines it, a disorder involving diminished social behaviors and elevated restrictive/repetitive behaviors?

In fact, new claims about evidence are made each time an article appears that reports data indicating motor difficulties in autism. Most recent are two articles by Bhat (2020 and 2021). Each of these—the two articles use the same database and draw similar conclusions—find evidence for motor difficulties in an overwhelming majority of children with autism (approximately 87%). The more recent article, Bhat (2021), also finds that the severity of motor difficulties correlates with autism symptom severity and degree of cognitive impairment.

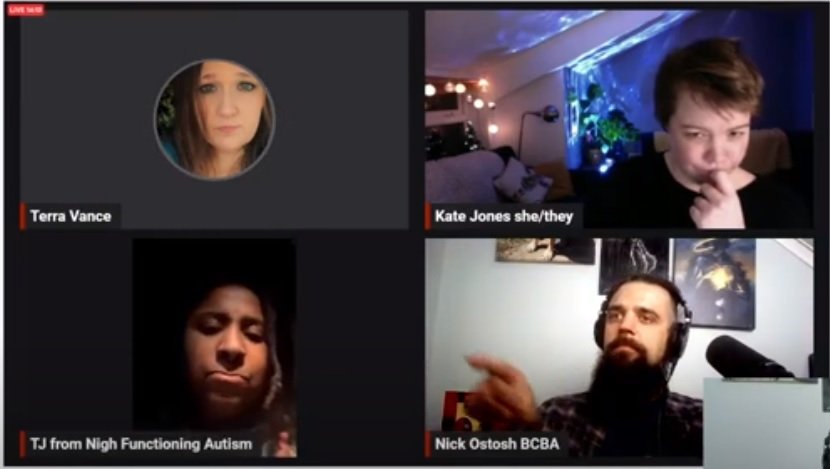

These articles have, predictably, been a big hit with FC proponents. In a recent YouTube debate between three proponents of RPM and a behavioral analyst, one of the proponents, implicitly citing Bhat’s research, claims (between the 11:25 and 13:00 minute marks) that a “giant sampling of autistic people” has found that “86% of autistic people have clinically significant apraxia.” She adds that “a lot of people with apraxia have severe motor disinhibitions,” which, she says, means that

They do movements and things that they don’t intend to do. They make faces. They say things that they didn’t intend to say.

But do either of the Bhat articles actually draw such conclusions?

As it turns out, there are several problems with the claim that 86% (or 87%) of individuals with autism have a “clinically significant apraxia” that includes “motor disinhibitions”:

1. Bhat’s data (drawn from the Simons Foundation’s SPARK database) was parent surveys (reliably unreliable), not clinical observations.

2. Only some of the survey questions addressed praxis/motor planning; the others focused more on fine motor and gross motor skills.

3. None of the survey questions addressed “motor disinhibition.”

4. While Bhat discussed fine and gross motor impairments in her conclusions, she made no specific references in either of these conclusions to motor planning difficulties/apraxia.

Let’s take a closer look at Bhat’s survey questions. Bhat used the 2007 Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ ’07). These questions probe skills like throwing, catching, and hitting a ball, jumping over obstacles, and various athletic skills (gross motor skills); and writing, drawing, and cutting skills (fine motor skills). None of these bear any obvious relationship to FC/RPM/S2C. They also probe motor planning skills like:

building a cardboard or cushion “fort,” moving on playground equipment, building a house or a structure with blocks, or using craft material.

And:

[being] quick and competent in tidying up, putting on shoes, tying shoes, dressing, etc.

Nor do any of these questions address difficulties that align with claims made by FC proponents. There’s nothing here, for example, that probes difficulties with pointing—not least the sort of difficulty that would require the wrist or elbow support seen in traditional FC. Indeed, as far as I know, the only people who claim (without evidence) that individuals with autism have significant difficulties pointing to things are FC-supporters like Morton Gernsbacher. Either the complete absence in the DCDQ of questions about pointing is an egregious omission, or pointing, even among those with significant motor challenges, is not a common difficulty.

What about the claim that “a lot of people with apraxia have severe motor disinhibitions” and therefore “do movements and things that they don’t intend to do.” To some extent, this sounds reasonable: if you have difficulty throwing a ball or cutting a shape out of paper, the problem, in some sense, boils down to unintended movements. You threw the ball along a trajectory that you didn’t intend, or cut out a shape that doesn’t look like the shape you intended, because your arms or hands or fingers didn’t move the way you intended them to. But none of this has any obvious relevance to FC/RPM/S2C.

What is relevant, on the other hand, is a second meaning of “do movements and things they don’t intend to do” that is artfully hidden behind the first. It goes back to my coinage of “intentional control”: the ability to inhibit one’s body from carrying out an unintended goal (e.g., inhibiting the urge to flap one’s hands or echo a favorite phrase) when it interferes with an intended goal. To some extent, this is a real phenomenon. Flapping (and other “stims”) and echolalia, both common in autism, are often reflexive rather than intentional. They can be difficult to suppress.

But FC proponents have more in mind than just this. To explain why what facilitated people type is so often at odds with their behavior—whether calling out “No more! No more!” or refusing pancakes—FC proponents have to include, as “movements they don’t intend to do,” much more than stims and echolalia. They also have to include actions that look pretty darn intentional to most of us. And these actions have to actively interfere with other acts that are intentional.

Consider the question about whether a child can construct a house out of blocks. A child with motor planning difficulties might build an amorphous object that doesn’t quite look like a house. A child with an “intentional control” problem—in the stronger sense of “intentional control” that FC proponents are cornered into believing in—might accidentally build a tower or an arch instead of a house. Or neatly print out the word “popcorn” when they meant to write “today”. Or clearly pronounce the word “dinosaur” when they meant to say “jacket.” Or point to the red square when they meant to point to the green one.

If all this sounds unlikely, it’s because it is. These are not instances of apraxia/motor planning. Nor do any of the articles on motor difficulties in autism describe anything that even comes close. The kind of mind-body disconnect that one would need to invoke—and that, indeed, FC proponents do invoke—is unattested in any empirical studies of autism.

Let’s climb down from these fantastical heights and conclude with a final claim about motor control—one that is especially popular with S2C supporters in particular. These folks claim that the reason that S2Ced individuals must rely on index-finger typing—as opposed to speech or ten-finger typing—is that they have significant problems with fine motor control. As Elizabeth Vosseller, the “inventor” of S2C, puts it:

We start by taking communication out of speech, and we teach purposeful movement by using the whole arm, taking it out of fine-motor, putting it in gross-motor…

To some extent, the Bhat papers support this strategy: Bhat finds significant difficulties with fine motor control in autism.

But there are two fatal problems. The first is that Bhat finds that difficulties with gross motor control in autism are nearly as prevalent and significant as difficulties with fine motor. The second is that pointing is a fine motor skill.

Indeed, in the YouTube debate, starting at around 14:00, the behavior analyst tries, repeatedly, to get this across—in part by demonstrating this by making pointing gestures at the screen. But the RPM proponents quickly dismiss him.

One says: “No, when you have movement from shoulder, that’s gross. If movement comes from shoulder, it’s gross. If it’s from the wrist down only, then it’s fine motor.”

Another chimes in with “Nick, you’re using your shoulder right now. Nick, you’re using your shoulder right now.”

The first, perhaps noticing that Nick’s shoulder is hardly moving at all, adds “and your elbow… your whole arm.”

Nick says “I believe it’s just the bottom half of my arm that’s moving.” He then suggests that they move on to new topics.

But that doesn’t happen until the main speaker pauses and says “Ok. Anyway. That’s gross motor, that’s not debatable.”

Of course, the main reason why this isn’t debatable is that if, on top of autism not being a mind-body disconnect, pointing is not gross motor but fine motor, then one more critical foundation for S2C comes crashing down.

REFERENCES:

Bhat A. N. (2021). Motor Impairment Increases in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder as a Function of Social Communication, Cognitive and Functional Impairment, Repetitive Behavior Severity, and Comorbid Diagnoses: A SPARK Study Report. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 14(1), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2453

Bhat A. N. (2020). Is Motor Impairment in Autism Spectrum Disorder Distinct From Developmental Coordination Disorder? A Report From the SPARK Study. Physical therapy, 100(4), 633–644.

Wilson, B.N., Crawford, S.G., Green, D., Roberts, G., Aylott, A., & Kaplan, B. (2009). Psychometric Properties of the Revised Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 29(2):182-202. https://dcdq.ca/uploads/pdf/DCDQAdmin-Scoring-02-20-2012.pdf

Read all three articles in this 3-part series:

Do facilitated individuals have motor difficulties that explain away our concerns about FC? Part 1

Do facilitated individuals have motor difficulties that explain away our concerns about FC? Part II